Introduction

Previously, in Part 1 of my Distributed Cache Series, I discussed Redis Cache, how it works, its benefits, limitations, and various trade-offs we need to think about before using Redis in production. In this part of the series, we will discuss Amazon MemoryDB and what makes it different from Redis. We will also examine what problem it solves over Redis and how it solves them. Again, we will discuss its benefits, limitations, and various trade-offs it provides.

Last month I came across this blog post by Marc Brooker where he discusses the paper Amazon MemoryDB: A fast and durable memory-first cloud database by Yacine Taleb, Kevin McGehee, Nan Yan, Shawn Wang, Stefan C. Muller, and Allen Samuels. This paper caught my interest because it addresses a fundamental problem in distributed caching: achieving strong consistency and durability.

Note: Please go through Part 1 first, before continuing to read this Part.

Redis Limitations

As discussed in the first part of the series, Redis has various limitations as well as benefits.

Redis lacks a durable replication solution that can prevent data loss when nodes fail or provide scalable, strongly consistent reads (notice here scalability, redis can provide strongly consistent READswith a single instance but with low availability and low scalability). To compensate for this, users often create complex data pipelines to ingest and durably store data in some persistence database before loading it into Redis. In cases of data loss, a separate process is required to rehydrate the cache, increasing complexity, costs, operational requirements, and reducing availability.

Redis puts lots of responsibilities on Redis Clients, Redis uses it for the discovery of shards and routing the request to that corresponding shard, making the client complicated. It also makes it impossible to have simple CRUD REST APIs, which abstracts away the complication of managing routing, sharding, consistency, and durability.

Redis uses a quorum-based system for both failure detection and the election of a new primary. However, this protocol doesn’t ensure consistent replica promotion because replication between the primary and replica nodes is asynchronous. During failover, the replica may not be fully synchronized with the primary, leading to potential data inconsistencies. The quorum-based approach also doesn’t provide a way to tackle the split-brain issue.

Redis offers lightweight persistence through point-in-time snapshots and on-disk transaction logs in the form of an Append-Only File (AOF). Snapshots serialize data to disk, while AOF logs all changes. In its strictest mode, AOF uses fsync() after every update which would synchronously flush the data buffer to the disk, ensuring durability and linearizability but reducing availability if the primary node fails. It only uses AOF files to recover a primary node after failure, although it’s very much possible that the node is not recoverable and data is permanently lost as the AOF files are stored locally only. Snapshot creation is also a very expensive operation that affects the availability of the system.

For a further and more detailed read on Limitations, you can refer to this.

What is MemoryDB?

Amazon MemoryDB is a fully managed, Redis-compatible, in-memory database service providing single-digit millisecond write and microsecond read latencies, strong consistency, durability, and high availability.

It’s a database service designed for 11 9s of enterprise-grade durability with fast in-memory performance. It delegates durability to a separate low-latency, durable transaction log service (Amazon Internal), enabling it to scale performance, availability, and durability independently of the in-memory execution engine(redis).

Novel Solution

The novel solution here that MemoryDB has implemented is the usage of a Multi-AZ transaction log (MTL) service (internal service to AWS). In short, what this transaction log service provides is a consensus, total order, and durability solution. The core concept here is that in Redis, control and data plane nodes used to be strongly coupled, but MemoryDB separates them, to scale them independently and decouple the availability and durability of the system. MemoryDB uses it to solve the following problem with Redis.

- Durability

- Leader Election

- Strong Consistency

- Split-Brain

- High Availability

MemoryDB streams the WRITEsto this MTL service synchronously which persists those WRITEsdurably across multiple AZs and is used by other replicas to fetch the data asynchronously.

As the WRITEsare ordered by the primary before sending to the MTL service, it provides strong consistency. During the primary failover, MemoryDB streams the past WRITEsfrom the MTL service until it reaches the current consistent state before becoming primary, providing strong consistency across failover.

For leader election, instead of using a quorum-based approach, MemoryDB uses this MTL service to reach a consensus on the new leader. This also helps MemoryDB completely avoid split-brain situations.

In addition to everything above, MTL also provides a separation of concern where the transaction logs can be used to scale the recovery, and point-in-time snapshot creation, independent of resources available on the primary node. This helps in delivering a system that has a low Recovery-Time-Objective (RTO) and doesn’t affect the production system as it used to during snapshot creation for Redis.

Transactional Log Service

Marc Brooker on his recent blog has explained this Multi-AZ Transactional Log Service and how it uses fencing to provide a more practical API interface for consensus in distributed systems. I wanted to share my perspective on how this service can be valuable, not just for this specific use case, but for a wide range of others as well.

MTL service provides the total ordering of the events in a distributed system.

WRITEs are sent to the MTL service concurrently.

Using the following APIs

API - Set I

write(payload) -> sequence number

read() -> (payload, sequence)

Order I: W1 -> W2 -> W3 -> W4

Order II: W2 -> W1 -> W4 -> W3

Both orders of WRITEs are possible along with many others. This makes the final ordering non-deterministic.

Non-deterministic total ordering, in general, real-world practical distributed systems are not very useful.

Distributed systems need deterministic total ordering to make sense of these WRITEs, otherwise, it’s just WRITEs overwriting each other causing race conditions. It’s very much possible in MemoryDB architecture to have an election where two nodes might try to become a leader, simultaneously.

Now, we want to make things deterministic with total ordering and maintain system correctness.

API - Set II

write(payload, seq1) -> seq2

read() -> (payload, sequence number)

The above set of API interfaces uses what’s called fencing. These APIs provide us a way to validate that clients know about all the WRITEs that have come before a particular WRITE, before it appends the new payload. This will make sure that only one of the concurrent WRITEs is successful and all others fail because of a mismatch in the last sequence number, so they will have to retry again after doing READ and repeat the above process. But this has one problem, this will require us to do a total of 20 API calls to do 4 WRITEs. It’s not really efficient.

Now, we want to make things efficient with deterministic total ordering and avoid sending two WRITEoperations at the same time for a key.

API - Set III

take_lease() -> (lease_id, expiry_time)

extend_lease(lease_id) -> new_expiry_time

write(payload, seq1) -> seq2

read() -> (payload, sequence number)

The above set of API interfaces uses a concept called leasing. An almost 35-year-old concept where only a leader/primary takes the lease which permits it to send the WRITE operations, any other node can’t execute the WRITE operation (only if it’s working as expected. Check Byzantine Faults).

Now, we want to make things work as it is, in the case of Byzantine Faults. We want to make a set of APIs that provides efficient deterministic total ordering in byzantine fault scenarios.

API - Set IV

take_lease() -> (lease_id, expiry_time)

extend_lease(lease_id) -> new_expiry_time

write(payload, seq1, lease_id) -> seq2

read() -> (payload, sequence number)

To make sure we maintain the correctness even during worst-case scenarios where we have malicious nodes or nodes with bugs in them, we need to identify which client actually has the current lease when it’s trying to do WRITE operation, for that, your system needs to validate the leaser_id for each WRITE operation.

Now, there are two ways to go about it. The first is to create a separate leasing service and a separate transactional log service and do an ACID transaction across two when a new lease is taken to make sure the WRITE operation validates against the correct lease_id, or you could just use a transactional log service to provide an interface that works for taking lease.

API - Set V

take_lease(new_lease_id, old_lease_id) -> new_lease_id

write(payload, seq1, lease_id) -> seq2

read() -> (payload, sequence number)

Here, what we doing is creating a log chain for the lease_id where you can only get the lease after the expiration time and if you have the old_lease_id. Only one node will be able to take a lease at a time changing the current lease_id and invalidating the old_lease_id.

MemoryDB Benefits

Consistency

MemoryDB ensures linearizability by synchronously propagating changes to the MTL service. And, as Redis doesn’t have Multi-Version Concurrency Control (MVCC) support, and instead of implementing one, MemoryDB implemented a tricky solution of blocking the response to the Client until the data is replicated and persisted by the MTL service across all AZs. It also blocks the corresponding dependent response of sequential READsto make sure the linearizability is maintained across read-after-writes.

An important point to note is that MemoryDB provides strong consistency only when both READsand WRITEsare directed to the primary node. To optimize performance, replication from the MTL service to replica nodes is asynchronous. As a result, reads-after-writes sent to the same replica by a client will appear linearly consistent from that client’s perspective. However, if the replica fails, read requests will be redirected to a new replica, which may be ahead or behind the original replica in terms of data.

However, the paper does not mention an issue related to linear consistency if/when clients switch between different replicas. Since replication occurs asynchronously and in an uncoordinated manner across replicas, clients might experience inconsistencies. For example, if a client queries replica R1 and sees KEY=VALUE1 at time t=0, then switches to replica R2 and sees KEY=VALUE2 at time t=1, and later returns to R1 to see KEY=VALUE1 again at time t=3, this can result in non-linear behavior in the system.

Leader Election

As Redis uses a majority-based quorum for the leader election, it can cause a split-brain issue as mentioned in part 1 of the series. When the majority of the primaries across shards detect a primary failure, they vote to elect one of its replicas as the new primary, using a ranking algorithm to select the most up-to-date replica based on the local view (which might not be true anymore) of each voting node. Here the voting nodes are only primaries across shards.

MemoryDB uses the MTL service’s specific API interface to do a leader election, maintaining leader singularity, and consistent failover where only nodes with the latest data can fight to become the leader in an election. MTL service’s specific API interface allows MemoryDB to build a leasing algorithm, generally used to avoid split-brain situations where only one leader holds the lease on writes. This also removes the need for a quorum to reach for a leader election, increasing the availability of the service during a leader election as it doesn’t have to wait for the majority.

Recovery

In MemoryDB, a recovering replica first loads a recent snapshot and then replays subsequent transactions. Unlike Redis, which requires a primary node for data restoration impacting CPU and Memory load on the primary, MemoryDB periodically creates snapshots and stores them durably in S3. This enables MemoryDB to recover committed data without needing a primary node. This process also enables multiple replicas to recover simultaneously, without a centralized scaling bottleneck, which enhances the system’s availability during recovery.

Slot Transfer

In Redis, slot ownership is managed and communicated via the eventually consistent cluster bus, which is prone to several failure modes that can lead to data corruption or loss.

MemoryDB eliminated the reliance on the gossip protocol-based cluster bus and instead implemented a Two-Phase-Commit (2PC) across two shards. Slot ownership is stored in the transaction log. Since slot transfers span multiple shards and each shard maintains its own transaction log, a single transaction log can’t handle the transfer. To atomically commit across the two separate shard logs, MemoryDB uses 2PC.

One thing that the paper doesn’t talk about is who is coordinating the 2PC between these two shards.

Summary

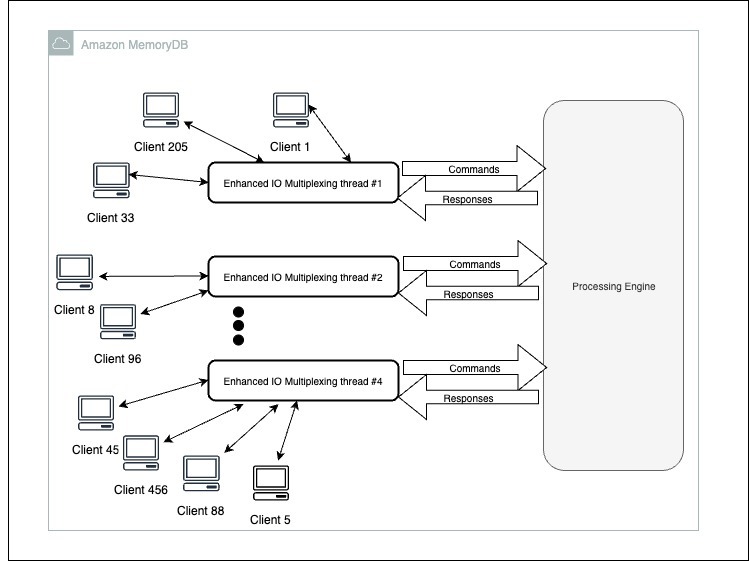

MemoryDB sees higher throughput for READsas compared to Redis, mostly because MemoryDB Enhanced IO Multiplexing aggregates multiple client connections into a single connection to the engine, improving processing efficiency and delivering higher throughput. Also, the quorum requirement was removed for writes/election/slot transfer from MemoryDB increasing its availability causing higher read throughput.

MemoryDB sees less throughput for WRITEsas compared to Redis as synchronous WRITEto MTL service has also become part of a WRITEoperation.

READ latency is comparable between MemoryDB and Redis. Although WRITElatency is higher in MemoryDB because of the synchronous WRITEto MTL service.

WRITEsto the MTL service.

Overall, I think there is an important lesson to learn here.

Leader election, strong consistency, and split-brain scenarios are all interconnected issues that arise in systems lacking consensus mechanisms. To address these problems, a consensus protocol can be integrated into the system. Essentially, adding a consensus mechanism involves incorporating an additional consensus layer into the existing system.

References

- Amazon MemoryDB: A fast and durable memory-first cloud database - https://www.amazon.science/publications/amazon-memorydb-a-fast-and-durable-memory-first-cloud-database

- Multi-Version Concurrency Control - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Multiversion_concurrency_control

- Distributed Cache Series - Part I - Redis - https://shubham-bansal.com/posts/distributed-cache-series-part-1-redis/

- Amazon MemoryDB - https://aws.amazon.com/memorydb/

- Redis - https://redis.io/

- MemoryDB: Speed, Durability, and Composition - https://brooker.co.za/blog/2024/04/25/memorydb.html

- Byzantine Faults - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Byzantine_fault

- Leases: an efficient fault-tolerant mechanism for distributed file cache consistency - https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/74851.74870

- MemoryDB Enhanced IO Multiplexing - https://aws.amazon.com/memorydb/features/